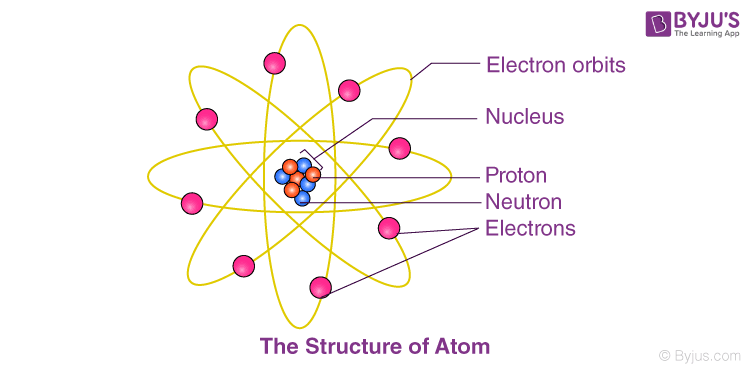

An atom containing one proton is a hydrogen atom (H). An atom containing 6 protons is a carbon atom. And an atom containing 8 protons is an oxygen atom. The number of electrons that surround the nucleus will determine whether or not an atom is electrically charged or electrically neutral. A neutral atom is an atom where the charges of the electrons and the protons balance. Luckily, one electron has the same charge (with opposite sign) as a proton. Example: Carbon has 6 protons. The neutral Carbon atom has 6 electrons. In chemistry and atomic physics, an electron shell may be thought of as an orbit followed by electrons around an atom's nucleus.The closest shell to the nucleus is called the '1 shell' (also called the 'K shell'), followed by the '2 shell' (or 'L shell'), then the '3 shell' (or 'M shell'), and so on farther and farther from the nucleus.The shells correspond to the principal quantum numbers (n. Electrons contribute greatly to the atom’s charge, as each electron has a negative charge equal to the positive charge of a proton. Scientists define these charges as “+1” and “-1. ” In an uncharged, neutral atom, the number of electrons orbiting the nucleus is equal to the number of protons inside the nucleus. An atom is the smallest unit of ordinary matter that forms a chemical element.Every solid, liquid, gas, and plasma is composed of neutral or ionized atoms. Atoms are extremely small, typically around 100 picometers across.

Our quantum computing lab is in collaboration with eight institutions on developing the world’s first neutral atom quantum computer. Proposed by Richard Feynman decades ago, quantum computers are seen as a successor of contemporary computers as they can theoretically factor numbers exponentially better than a contemporary computer. This makes their use in decoding a prime asset. However, up until now all other quantum computers utilize charged atoms, or ions. What makes our project special is that we use neutral atoms, which can be easily held in close confinement with each other. This cannot occur in ion based quantum computers due to strong interactions. The Anderson group is in the process of creating a two-dimensional array of Cesium (Cs)atoms. The theoretical maximum lifetime of each Cs atom in the array is 100 seconds. This lifetime is long enough that we can continuously monitor atom loss and reload any atom at individual sites in the array as needed. Our project is aimed at taking a single Cs atom from a magneto-optical trap (MOT) of millions of Cs atoms and transporting it to an empty array site. Thus, a constant cycle of Cs atoms will always ensure the array will have a full supply of Rydberg Cs atoms. It is this Cs array that will serve as the qubits necessary for quantum algorithms.

This project relies critically on the understanding and implementation of laser cooling and optical dipole trapping. We utilize the fact that a photon carries with it energy and momentum. Having multiple laser beams intersecting at a single point can transfer momentum from the light to atoms in such a manner that the atoms become confined. A quadruple magnetic field aids in creating a region of space where the forces of the lasers and the magnetic field combine to trap the atoms in a MOT. Because the atoms are confined in space, their thermal motions are very small and thus the temperature of the atom cloud is cooled to microkelvin temperatures. We use this procedure in order to create a reservoir of available Cs atoms needed for transport into the array. Our high powered class IV lasers are used to intersect a sample of Cs vapor and create a trapped cloud of hundreds of millions of Cs atoms in a MOT. At this point, we have a cloud of Cs atoms at a fraction above absolute zero. The top image below depicts our laser system used for trapping and transporting Cs atoms into the array where the location of the MOT vacuum cell is circled. The bottom images depict a close-up of the MOT vacuum cell (left) and fluorescence from a Cs MOT (right).

Neutral Atom Of Lithium

After a Cs MOT is created, we move some of the trapped Cs atoms using a moving optical molasses. We produce this moving molasses by counter-propagating laser beams at a 45 degree angle and guide the atoms using a vertically oriented dipole beam. The frequencies of the counter-propagating beams are precisely calibrated to produce a net force upward on the Cs atom cloud, which tosses the Cs atoms upward as an atomic fountain in the MOT cell. The dipole beam then uses its dipole force to aid in attracting and guiding the fountain upward. The moving molasses can displace atoms from the MOT to the third chamber. Progress was made to allow this moving molasses to traverse a distance of approximately 5 cm from the MOT cell to the third chamber. Absorption imaging was done to track the moving molasses of Cs atoms as shown in the image below where the thin line on the right-hand side of the images shows Cs atoms at different times.

The next course of action with the moving molasses is to create a reservoir in the third chamber utilizing a crossed dipole trap. Using the reservoir of Cs atoms in the third chamber, Cs atoms are further transported into the AQuA chamber. This chamber is a hexagonal vacuum cell with beams intersecting on all sides (see the schematic depicted below). The MOT chambers and the AQuA chamber comprise the AQuA cell, which is a state-of-the-art vacuum chamber science cell that is designed to isolate all optical components from the Cs array. This design keeps the interior pressure of the cell at the nanotorr level and ultimately enables each atom in the array to “talk” to each other effectively. This “talking” is made possible by having each Cs atom entangled with its neighboring atoms and serves as the heart of a quantum computer and truly separates a quantum computer from a classical computer. Our entangled Cs atoms can now act as qubits, or “quantum bits.” Similar to classical bits in a computer, a qubit can store information. What separates a bit from a qubit is that a qubit can store two pieces of information at the same time, while a bit can only store one piece of information. This is made possible by using the quantum principle of superposition. This allows the quantum computer to store an exponentially greater amount of information compared to a classical computer.

How can we make this array where Cs qubits “talk” to each other? We use a multitude of laser beams to accomplish this, including visible spectrum blue and green wavelengths along with infrared laser beams. This region of intersection is the location of the qubit array and will be the site for the imaging necessary to monitor the array. The Anderson group specifically is aimed at creating a 2 x 3 qubit array of Cs atoms; however, the overall project aims at making an 8 x 8 qubit array of Cs atoms.

This project still has years left before completion and is growing in scientific intrigue with each passing day. People working on this project are gaining deep knowledge in lasers, advanced quantum mechanics, laser cooling, vacuum systems, manipulating ultra-cold atoms, and even quantum algorithms.

In the race to build the first, useful, large-scale quantum computer, researchers are exploring many different routes, each with their own strengths and limitations. Approaches that use neutral atoms offer a scalable system, but the consistency of atom interactions—their quantum fidelity—lags behind that of other architectures. Now, building on recent improvements in controlling atoms in highly excited “Rydberg” states, Harry Levine at Harvard University and colleagues have demonstrated a neutral-atom quantum computer that achieves fidelities rivaling its highest-performing competitors.

The team performed quantum logic operations on clusters of two or three closely spaced rubidium atoms held individually in optical tweezers. The atoms became entangled when one of them was excited by a laser into a Rydberg state—a state where the outermost electron is highly energized. This transition also prevented the atom’s neighbors from being excited at the same time, a situation that is essential for creating logic gates comprising two and even three quantum bits (qubits). The ability to host multiqubit gates indicates that this platform may be especially efficient at implementing certain quantum algorithms.

So far, Levine and colleagues have manipulated a row of five two-atom clusters simultaneously, but they see no barriers to expanding the setup to create 2D lattices of dozens or even hundreds of qubits. (Another group, for example, has experimented with a square array of neutral-atom qubits.) In this configuration, lasers would pick out two or three adjacent atoms to implement high-fidelity, two- or three-qubit gates as required.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Marric Stephens

Marric Stephens is a freelance science writer based in Bristol, UK.

Parallel Implementation of High-Fidelity Multiqubit Gates with Neutral Atoms

Harry Levine, Alexander Keesling, Giulia Semeghini, Ahmed Omran, Tout T. Wang, Sepehr Ebadi, Hannes Bernien, Markus Greiner, Vladan Vuletić, Hannes Pichler, and Mikhail D. Lukin

Published October 22, 2019

Subject Areas

Related Articles

Atomic and Molecular PhysicsLaser-Cooled Atoms and Molecules Collide in a Trap

An experiment shows the circumstances under which ultracold atoms are quick to kick molecules out of a trap, providing clues for how to use atoms as a refrigerant for molecules. Read More »

Optics

OpticsOptics Bench on a Graphene Flake

A nanoscale, graphene-based device takes advantage of the wave nature of electrons and provides a level of control that will be useful for quantum computers. Read More »

Quantum PhysicsNeutral Atoms

Qubits Could Act as Sensitive Dark Matter Detectors

Neutral Atom Of Lithium

A detector made from superconducting qubits could allow researchers to search for dark matter particles 1000 times faster than other techniques can. Read More »